As part of my Simply Explained series, I’ve been covering a range of student-centered instructional approaches, from project-based learning to experiential and inquiry-based learning.

Today, I cover Game-Based Learning (GBL), a topic that has been particularly influential in my work as an educator and researcher. James Paul Gee is one of the key theorists in this field, and his work has profoundly shaped my understanding of GBL. I was fortunate to have scholars like Dr. Colin Lankshear and Dr. Michele Knobel on my doctoral committee, both of whom introduced me to Gee’s groundbreaking insights.

Although my main focus was on his discourse analysis framework, his theorizations around GBL have also been instrumental in shaping my approach to teaching and learning. Gee’s books, “Situated Language and Learning” (2004) and “What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy” (2004), are essential reading for anyone interested in the powerful intersection of gaming and education.

In this post, I have pulled together key insights from the literature to present a straightforward overview of game-based learning, including its benefits, theoretical foundation, core elements, and common misconceptions. I hope this resource provides a clear starting point for educators looking to integrate GBL into their teaching.

Related: Experiential Learning Simply Explained

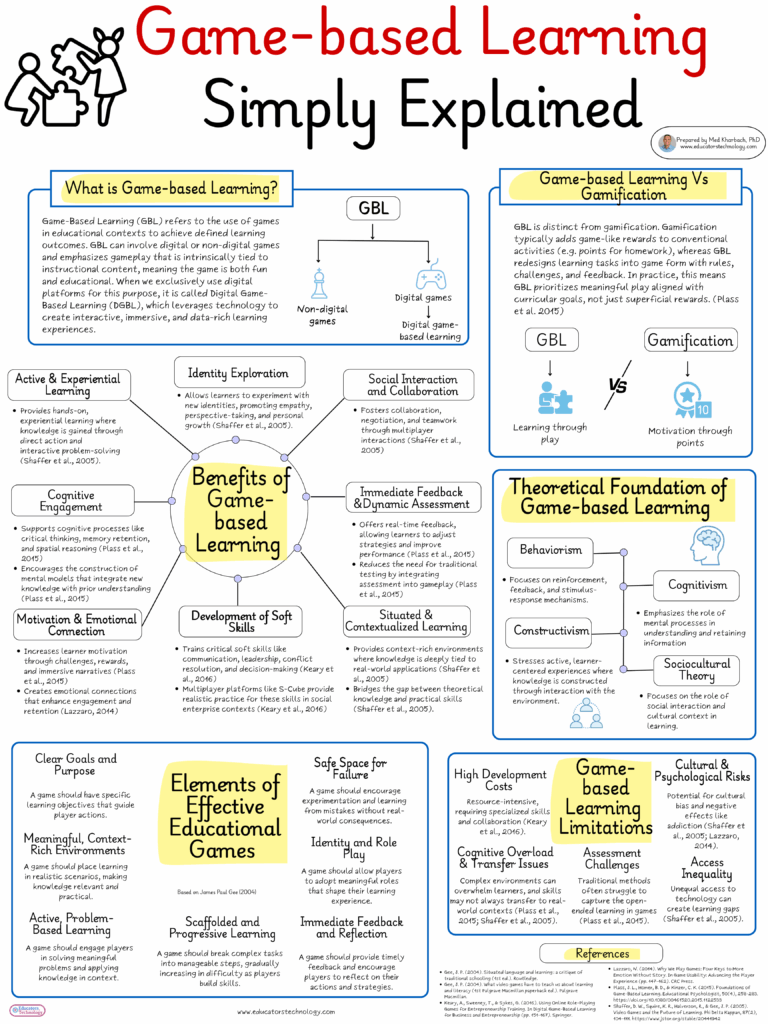

What is Game-based Learning?

Game-Based Learning (GBL) refers to the use of games in educational contexts to achieve defined learning outcomes. GBL can involve digital or non-digital games and emphasizes gameplay that is intrinsically tied to instructional content, meaning the game is both fun and educational.

When we exclusively use digital platforms for this purpose, it is called Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL), which leverages technology to create interactive, immersive, and data-rich learning experiences.

Game-based Learning Versus Gamification

Plass et al. (2015) distinguish between game-based learning (GBL) and gamification, emphasizing that while both approaches use game-like elements, their educational focus differs significantly. Gamification refers to the use of game elements, like points, badges, and incentive systems, to motivate learners to engage in tasks they might otherwise find unappealing.

For example, math homework can be gamified by adding point systems or rewards to encourage completion. In contrast, GBL involves a deeper integration of game mechanics, where the learning activity itself is redesigned to incorporate meaningful play, including rules, challenges, and artificial conflicts, making the learning process more engaging and immersive. This difference highlights that gamification adds game-like features to existing tasks, while GBL fundamentally rethinks the learning experience through the lens of game design.

Theoretical Foundation of Game-based Learning

The theoretical foundations of game-based learning (GBL) draw on several key learning theories, each contributing to the way games can effectively support education. Behaviorism emphasizes reinforcement and feedback, focusing on the relationship between stimuli and responses.

In GBL, this is often reflected in game mechanics that provide immediate, corrective feedback for right or wrong actions, reinforcing desired behaviors through points, levels, or rewards (Skinner, 1958). For example, language learning apps like Duolingo use this approach by offering instant feedback and rewards to motivate continued practice.

Cognitivism takes a different approach, emphasizing the importance of mental processes in understanding and retaining information. In GBL, this means designing tasks that challenge players to build mental models, process multiple types of information, and solve complex problems. Many strategy games, like Civilization or Portal, support this by requiring players to plan ahead, analyze situations, and adapt their strategies based on ongoing feedback (Plass et al., 2015).

Constructivism, on the other hand, stresses active, learner-centered experiences where knowledge is constructed through interaction with the environment. Games like Minecraft or simulation-based environments allow players to set their own goals, explore open-ended problems, and construct their own learning paths, reflecting the core principles of this theory (Vygotsky, 1978).

Finally, Sociocultural Theory focuses on the role of social interaction and cultural context in learning. Massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) like World of Warcraft exemplify this approach by fostering collaboration, communication, and collective problem-solving among players, creating rich social contexts for learning (Gee, 2003).

Benefits of Game-based Learning

Game-based learning has a wide variety of educational benefits, here are some of them:

- Active and Experiential Learning

- GBL provides learners with opportunities for hands-on, experiential learning, where knowledge is gained through direct experience and interactive problem-solving (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Cognitive Engagement and Mental Model Development

- Games can support cognitive processes like critical thinking, memory retention, and spatial reasoning by encouraging players to build mental models and integrate new knowledge with prior understanding (Plass et al., 2015).

- This cognitive engagement is enhanced when games align with established learning theories, including behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism (Plass et al., 2015).

- Motivation and Emotional Connection

- GBL can increase motivation through challenges, rewards, and immersive narratives, which keep learners engaged and invested in their progress (Plass et al., 2015).

- The emotional impact of gameplay, including the sense of achievement and connection to the game world, further enhances learning outcomes (Lazzaro, 2014).

- Development of Soft Skills

- GBL platforms like S-Cube focus on soft skills training, including communication, leadership, conflict resolution, and decision-making, which are critical in real-world professional settings (Keary et al., 2016).

- The use of multiplayer online role-playing games (E-MORPGs) helps learners practice these skills in simulated environments that mirror real-life social interactions (Keary et al., 2016).

- Situated and Contextualized Learning

- Games provide situated learning environments where knowledge is contextually grounded, making it more relevant and meaningful for learners (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- This approach helps bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, enhancing retention and transfer of skills (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Immediate Feedback and Assessment

- Games provide real-time feedback, allowing learners to adjust their strategies and improve their performance as they progress (Plass et al., 2015).

- This dynamic assessment model can reduce the need for traditional testing and make learning more interactive and responsive (Plass et al., 2015).

- Social Interaction and Collaboration

- Multiplayer games create opportunities for collaboration, negotiation, and collective problem-solving, fostering teamwork and communication skills (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Online game communities also provide support networks and peer learning opportunities that extend beyond the game itself (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Identity Exploration and Role Play

- Games allow learners to experiment with new identities and roles, promoting empathy, perspective-taking, and personal growth (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- This identity exploration is a key component of professional development and self-discovery in educational contexts (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Scalable and Flexible Learning

- Digital GBL platforms like S-Cube can be easily adapted for different learning contexts, from classroom settings to corporate training, offering scalable educational solutions (Keary et al., 2016).

- Innovative Assessment Opportunities

- Games offer embedded assessment options, capturing both process and outcome data, providing a more comprehensive view of learner progress (Plass et al., 2015)

Limitations

Here are some of the main limitations of Game-Based Learning (GBL):

- High Development Costs and Technical Complexity

- Creating high-quality educational games can be expensive and time-consuming, often requiring interdisciplinary teams of designers, educators, and developers (Keary et al., 2016).

- Technical challenges, such as maintaining immersive experiences while integrating educational content, can limit widespread adoption (Plass et al., 2015).

- Cognitive Overload and Distraction

- The rich, interactive environments of games can sometimes overwhelm learners with too much information, leading to cognitive overload (Plass et al., 2015).

- The presence of non-educational elements or excessive gamification can distract learners from the primary learning objectives (Plass et al., 2015).

- Lack of Transferable Skills

- Skills developed within game contexts may not always transfer effectively to real-world situations, particularly if the game environment does not closely mimic real-world tasks (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Assessment Challenges

- Assessing learning in game-based environments can be difficult, as traditional testing methods are not always compatible with the open-ended, exploratory nature of games (Plass et al., 2015).

- There is often a gap between in-game performance and real-world competence (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Access and Equity Issues

- Not all students have equal access to the technology required for digital games, leading to potential inequalities in learning opportunities (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- The high cost of hardware and software can be a barrier for low-income schools and communities (Keary et al., 2016).

- Resistance from Educators and Institutions

- Many educators remain skeptical of the educational value of games, viewing them primarily as entertainment rather than serious learning tools (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Integrating games into traditional curricula can be challenging, as it requires significant changes to teaching methods and assessment practices (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- Cultural and Content Bias

- Some games may reflect cultural biases or stereotypes, potentially reinforcing harmful assumptions if not carefully designed (Shaffer et al., 2005).

- The global reach of digital games also raises concerns about cultural relevance and appropriateness for diverse learners (Plass et al., 2015).

- Ethical and Psychological Risks

- Excessive gaming can lead to negative psychological effects, including addiction, social isolation, and reduced physical activity (Lazzaro, 2014).

- There are also ethical concerns about the use of games for sensitive subjects or high-stakes assessments (Shaffer et al., 2005)

Conclusion

Game-Based Learning (GBL) is a powerful framework for deep, meaningful learning. Grounded in well-established educational theories like behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, and sociocultural learning, GBL provides a rich, interactive environment where learners can explore, experiment, and reflect.

However, while GBL offers significant benefits, from increased motivation to real-time feedback and social collaboration, it also comes with challenges. High development costs, cognitive overload, and access inequalities are just a few of the barriers that educators must navigate when integrating games into their teaching. Ultimately, GBL’s success depends on thoughtful design, a clear alignment with learning goals, and a deep understanding of the theories that underpin effective learning.

References

- Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning : a critique of traditional schooling (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Gee, J. P. (2004). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy (1st Palgrave Macmillan paperback ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Keary, A., Sweeney, T., & Sykes, G. (2016). Using Online Role-Playing Games for Entrepreneurship Training. In Digital Game-Based Learning for Business and Entrepreneurship (pp. 151-167). Springer.

- Lazzaro, N. (2014). Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion Without Story. In Game Usability: Advancing the Player Experience (pp. 147-162). CRC Press.

- Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

- Shaffer, D. W., Squire, K. R., Halverson, R., & Gee, J. P. (2005). Video Games and the Future of Learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 87(2), 104-111. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20441942

The post Game-based Learning Simply Explained appeared first on Educators Technology.